I recently took a course run by Thomas Moore, an author and therapist influenced by James Hillman and C.G. Jung. We dove into Archetypal Psychology, Greek mythology, the arts, and much more.

The course stirred my imagination and breathed new life into fundamental questions. What characterises the human soul? What is the nature of suffering? How can we support our fullest flourishing?

While considering these questions, I was also reading Thomas Moore’s book Dark Nights of the Soul. One thing that became clear to me was the importance of language; how we speak about the big questions in life is crucial. Words are not just inert tools. They shape and reshape our imagination. They have a legacy and life of their own, and there is no shortage of concepts vying for supremacy.

I recently noticed, for instance, how often the word ‘work’ crops up in the therapeutic space: inner work, shadow work, parts work, soul work. Does this reflect our collective obsession with the Herculean and the heroic? I wonder if this has given me the idea that salvation comes through Protestant work ethic and Victorian discipline. To be free, must I slog it out with my demons and endure years of hard labour?

I also note the preponderance of terms that imply a peak destination or idealised state: wholeness, integration, adjustment, self-actualisation, self-realisation, enlightenment, awakening. Is it not tempting to concretise these notions, rendering them lifeless through blind subservience?

Words, therefore, can be the difference between an imaginative approach to life on one hand, and the stasis of fundamentalism on the other. I know this from experience. When I am suffering, the wrong words can corrode the soul, but the right ones can plant hopeful seed ideas. What form of language, then, might we invoke?

In Dark Nights of the Soul, Thomas Moore recommends invoking the language of poetry, which takes us into a timeless, mythic realm. This is the realm of image, symbol and metaphor. Here is a passage I found inspiring:

“Everyone around you expects you to describe your experience in purely personal or medical terms. In contemporary society we believe that psychological and medical language best conveys the experience we have of a dark night. You are depressed and phobic; you have an anxiety disorder or a bad gene. But perceptive thinkers of other periods and places say that good, artful, sensuous, and powerful words play a central role in the living out of your dark night. Consider this possibility: It would be better for you to find a good image or tell a good story or simply speak about your dark night with an eye toward the power and beauty of expression.

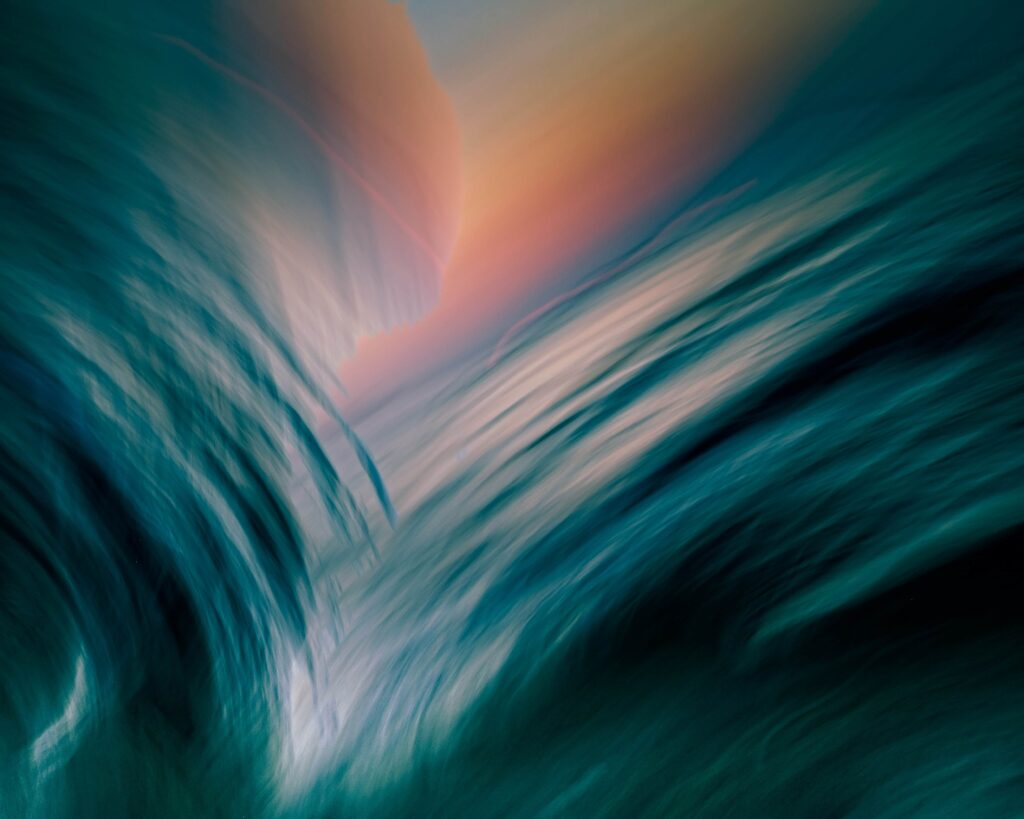

Poetic language is suited to the night sea journey, because the usual way of talking is heroic. We naturally speak of progress, growth, and success. Even “healing” may be too strong a word for what happens in the soul’s sea of change. The language of popular psychology tends to be both heroic and sentimental. You conquer your problems and aim at personal growth and wholeness. An alternative is to have a deeper imagination of who you are and what you are going through. That insight may not heal you or give you the sense of being whole, but it may give you some intelligence about life.”

I have found this to be true. The poetic approach to life does not shoehorn me into a convenient story or an arbitrary diagnostic category. Neither does it condition me to ‘work through’ my problems or trivialise experiences that touch me to the core. Rather, poetry keeps me open and alive. It helps me speak from the perspective of soul, including its multiplicity, its infinite complexity, its depth and naked suffering. It keeps my gaze on that “bandaged place” Rumi spoke of – the place where light enters.

The negative capability

Shifting towards a poetic consciousness is not about making life easier or more comfortable. To me, it’s about embracing the mystery and learning to cope with the ambiguities and paradoxes of life. John Keats spoke of the ‘Negative Capability’ – the ability to “be in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

I find this very challenging. When I am moved – truly moved – by a dream image, or a piece of music, or an actual line of poetry, something in me resists transformation before long. Ego knows it is just a cork bobbing on an unfathomable ocean of primal mystery. Suddenly, that well-meaning platitude or psychological concept looks like an attractive way to defend against my fear of the potent, transformative image.

I am still learning to lower those defences. For instance, opportunities often arise in conversation with loved ones. Something will come up that challenges me to ‘be with’ rather than ‘react against’ the imagery presented to me. They might express a difficult emotion or recount a distressing story.

It’s always tempting to make the images go away, dispelling the living poetry of the moment. I might reach for the shot of morphine, professing that “every cloud has a silver lining” in order to numb our shared pain. Or, if I’m not careful, I might find myself playing diagnostician, analysing the situation until it is no longer felt to be threatening. “Tell me the facts again so we can get to the bottom of this.” But there may be no ‘bottom’ to the experience, no single ‘right’ thing to do, no prescription for happiness.

As Moore says, the poetic approach to life may not heal or bestow wholeness, but it may help us get into relationship with more of ourselves and others. It may feed the imagination but not necessarily the Ego; soul enrichment and ‘working on my personality’ do not always walk hand in hand. Wisdom emerges when we engage with the poetic side of life and step into the mist and mystery of our soul in all its paradox.