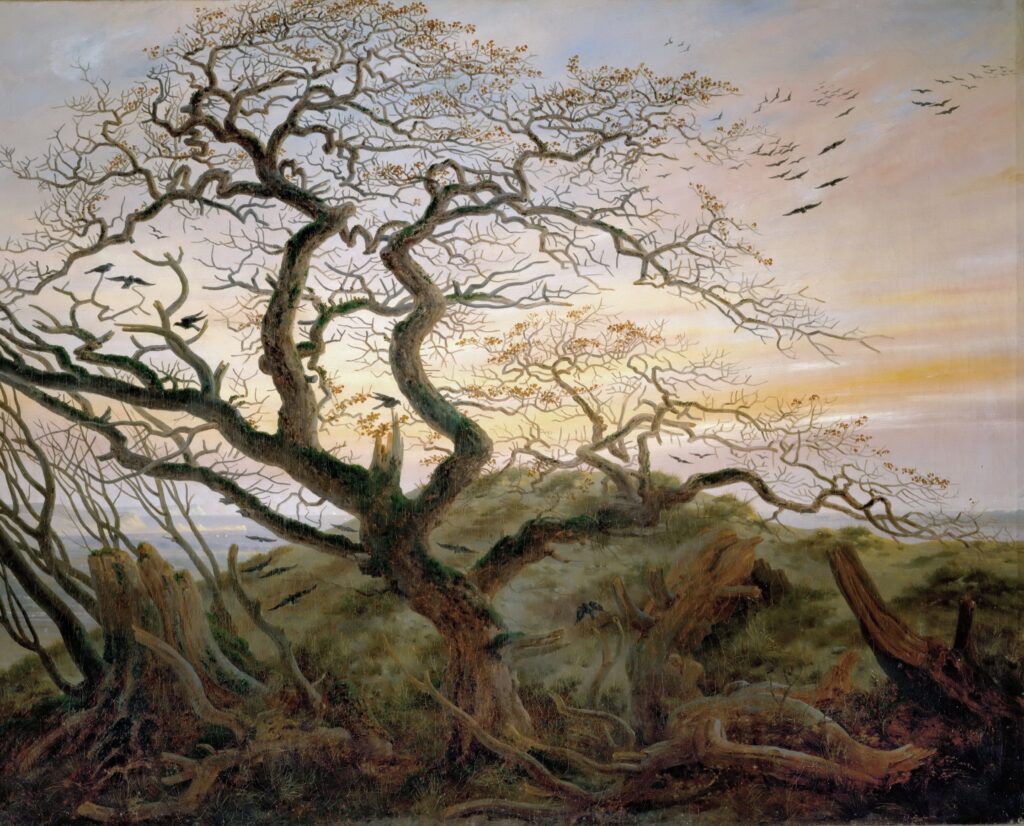

Close to my home, there is a peaceful nature trail. This summer I have walked on it most days, picking up some new impression each time. Recently, a magnificent oak tree caught my attention. I was disarmed by the appearance of its many crooked branches, zig-zagging into the sky at jagged angles.

Knowing that nature has much to teach, I asked myself what message this oak tree, this unique being, wanted to impart. Why was ‘crookedness’ seeking me out in that particular moment? The following is a brief meditation on this question.

The taboo against crookedness

Standing before the tree, my imagination was stirred. One of the first images that came to mind was of my posture. For many years, I have been experiencing on-off tension and pain in my lower back. If I go a long time without caring for this tension, it pulls my pelvis and spinal column out of alignment, and I tend to chastise myself for not doing enough to ensure I have an ‘ideal’ posture.

As a society, we are quite rigid about how people ought and ought not to look. Straight, symmetrical features are at the forefront of these standards. Misaligned teeth, wonky noses and hunched postures must all be corrected if one is to fit in and be seen as desirable. Yet in the refreshing presence of this proud old tree, internalised voices instructing me to stand tall and pin my shoulders back now seemed fearful and brittle.

But the taboo against crookedness is not limited to the physical. Both literally and symbolically, we are encouraged to hide our imperfections, our unshapely flaws, and ultimately any sign of psychospiritual wounding. This moralism is laid bare in the English language itself, where the sanctification of straightness becomes obvious. A ‘crook’ is an indecent person. We must stick to the ‘straight and narrow’ in order to avoid becoming a ‘deviant’. And someone who is ‘bent’ has supposedly been corrupted, sexually or otherwise.

Embracing crookedness

I am currently rereading the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu. The following lines, from Verse 22, are relevant to the discussion so far:

If you want to become whole, let yourself be partial.

If you want to become straight, let yourself be crooked.

If you want to become full, let yourself be empty.

Perhaps I had encountered a Taoist oak tree. Did it want to loosen my one-sidedness? In a little satori moment, its wisdom was immediately clear: “Relax! No need to keep posturing! Let yourself be like me – bent out of shape by necessity!”

If I place a ban on the experience of being partial, crooked or empty, I also rule out the genuine experience of wholeness, straightness and fullness. How could it be any other way? Opposites define each other. What is beauty without ugliness? What is joy without sorrow?

On the somatic level, this realisation has brought a new level of calm to my self-care routine. When practising qigong, yoga or sitting meditation, I feel less urgency to make something happen by force. As I patiently hold bodily tensions and restless thoughts in awareness, I let go of the need to change them.

This attitude does not preclude transformation – accepting the places in me that hurt the most, and noticing how life has bent me out of shape, does not mean I automatically succumb to fatalism. Can I both accept my symptoms, my crooked situation, my sense of lostness, and welcome it all as raw material, prima materia, for the alchemical process?

Like my friend the oak tree, I will keep practising this subtle art as best I can.