Whenever I watch The Truman Show, it puts me in a trance.

This film is a masterpiece, packed with multiple layers of symbolism and meaning. As the years go by, it only feels more relevant, Truman’s journey more profound.

I’ll explain in this post why The Truman Show strikes a chord with me, and in the process, unpack three powerful moral lessons.

synopsis

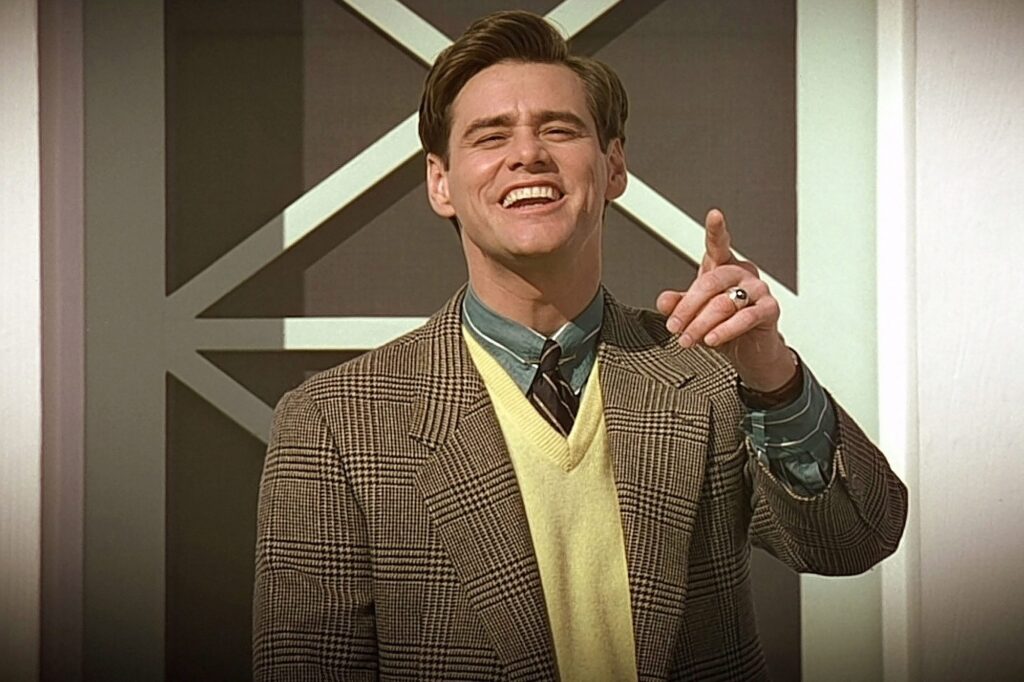

The Truman Show picks up with a day in the life of Truman Burbank. Living on the picture-perfect island of Seahaven, he has it all: a respectable job in insurance, a gorgeous house, a beautiful wife, and so on.

Truman seems upbeat on the outside. But he also yearns for adventure; having never left the island, he longs to visit the exotic islands of Fiji.

Midway through the film, cracks start to appear in Truman’s reality and he enters a period of deep questioning. Why does is he always at the centre of bizarre coincidences? Is he living in a dream? A nightmare? Are his loved ones really on his side?

Truman interrogates Meryl, his wife. But she dismisses him, which only makes Truman more paranoid. So he digs even deeper – an explorer at heart, Truman won’t drop his hunt for the truth.

As the audience, we then discover that truth: Truman has been living within the confines of an artificial dome since birth. The unwitting star of a global reality TV show, his every waking moment is being broadcast to billions. Everyone around him is an actor hired by a giant corporation to maintain a facade. This corporation, run by the enigmatic Cristof, even controls the weather.

Truman becomes spooked enough to attempt a bold escape, and he sets sail in spite of his intense fear of open water. Out of desperation, Christof generates a deadly storm which almost drowns Truman live on TV. But he prevails.

In the surreal final scene, Truman’s boat collides with the wall of the dome, painted to resemble a cloudy sky. He walks along the edge, reaching an exit door.

Christof now speaks to Truman directly, his voice booming from the sky. He lays out a choice: Truman can return to the safe, fabricated version of reality created just for him. Or he can head into the real world (which earlier in the film, Cristof calls ‘the sick place’).

What does Truman do? In a triumphant, courageous moment, he leaves it all behind and steps into the unknown.

3 life lessons from The Truman Show

It’s easy to get distracted by The Truman Show’s Big Brother theme, but the film’s lessons land much closer to home. In a sense, each of us is Truman Burbank. Like Truman, we’re told who to be, what to think, how to act, what to pursue, and what we’re capable of.

Consider these parallels between Truman and the average person:

- Pressure to conform: like Truman, we face enormous pressure to align with values we did not consciously choose.

- Conditioned perception: like Truman, we are conditioned to perceive reality in a very particular way, with the truth often hiding in plain sight.

- Confronting demons: like Truman, we have to face our fears if we want to start discovering who we are and seeing reality for what it is.

Perhaps these parallels explain why the film chimes with me. Even with the movie’s fanciful premise, there’s something relatable about Truman’s journey.

That said, here are three life lessons from The Truman Show that continue to inspire me.

Lesson 1: Beware the tyranny of conformity

The Truman Show illustrates beautifully the human drive to pursue truth, authenticity, and meaning. As Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl documents in Man’s Search For Meaning, this drive is unstoppable, even when the outside world tries to subdue it.

I’m talking about the ‘self-actualising tendency’ – our impulse to walk the path of becoming who we truly are rather than who we’re supposed to be. This is a lifelong process with no definitive endpoint.

For that journey to begin, we must outgrow our conditioning. The result can be turbulence: we yearn to develop personal values congruent with our true nature on one hand, but on the other we’re seduced by the potent (and often antagonistic) drive to conform.

Truman’s world portrays this dynamic to the extreme, with the pressure to conform most clearly represented by modern Western values, materialism chief among them.

In an early scene, for example, Truman discloses to Marlon a deep desire: he wants to ‘get out’. Out of his job, out of the city, and off the island. In response, Marlon chides him, “Out of your job? What the hell is wrong with your job? You have a great job, Truman. You have a desk job. I’d kill for a desk job.”

Later scenes follow a similar pattern: Truman expresses an authentic desire, which the cast and crew conspire to squash. In one scene, when Truman brings up the idea of going to Fiji, Meryl brushes him off as an idealistic teenager.

But developmentally, Truman sort of is a teenager. And not by accident – at every turn, the show has hindered his self-discovery. In turn, Truman is disconnected from life, with no solid sense of himself. His life rings hollow because it’s a life he has been conditioned to value, with conformity being the main weapon of control.

Our world isn’t so different. If we’re to grow, we must override our drive to conform. It’s no easy feat, especially with powerful entities (governments, corporations, elites) hell-bent on chaining us to self-serving narratives.

To set ourselves free, we must stray from the perceived safety of the pack. Avoiding this inner call ushers in a form of death. Not physical death, but psychospiritual death – a slow and steady disintegration of the self. Truman recognises this risk and acts instinctively.

Here’s the lesson: I must be wary of the drive to conform. On my deathbed, I won’t wish I had been more obedient, more cautious, or more inhibited. I’ll wish I had ventured out more, spoken up at the right moment, and stepped outside the status quo.

Lesson 2: To find your soul, lose your mind

You probably haven’t heard of ‘drapetomania’. That’s a good thing.

Coined in 1851 by American physician Samuel Cartwright, this ‘mental illness’ was put forward to explain why enslaved people kept trying to flee their captors. Cartwright deemed the life of a slave to be such an improvement that to reject it signalled madness!

Even at that time, drapetomania was recognised as hogwash. But this practice of relegating understandable suffering to the land of ‘illness’ certainly lives on in society, albeit in less overt form. In short, the line between sanity and insanity is an arbitrary one.

Take the experience we call ‘depression’. In a world obsessed with economic growth, it isn’t surprising that depression is medicalised. It doesn’t align with the economic imperatives of the day, namely to be a productive worker no matter the personal, social or emotional costs. But perhaps the suffering of depression has a purpose. Could it be to make us aware of how sick society is, so we can take action?

“It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

In the same way, Truman’s suffering has a purpose: it compels him to discover the truth.

We observe his first dance with that truth in the flashback where he meets ‘Lauren Garland’, real name Sylvia. Their connection is instant, spontaneous, and undeniably real. In contrast, Truman’s relationship with Meryl represents all that is forced/false in Truman’s world.

Although Sylvia is swiftly removed by her so-called father, and written off as psychotic, it’s too late: the seeds of truth have been sown. From then on, the only thing Truman finds solace in is his dream of escaping to Fiji, where he believes Sylvia to be. Sylvia symbolises the truth.

Midway through the film, Truman’s disillusionment gathers momentum. More cracks appear in his fabricated, controlled reality. Why is the man with flowers walking around and around the block on autopilot? Why did Meryl cross her fingers in their wedding photo?

As the illusion begins to falter, Truman enters a period of necessary breakdown. Quite literally – his perception of reality is breaking apart, fragmenting into pieces. Unable to piece together those fragments, Truman cycles through fear, loneliness, dejection, paranoia, and confusion.

This culminates in Truman taking Meryl for a joyride to Atlantic City. In one of my favourite scenes, he circles the roundabout shouting, “somebody help me, I’m being spontaneous!” out the car window.

Meryl frames Truman’s behaviour as him being ‘unwell’. But his spontaneity signals an impending awakening. As the viewer, I usually rejoice at this point – the grip of conformity is beginning to weaken. Truman is coming alive.

Finally, Truman leaves everything behind to pursue the truth. On his boat we see him cradle a collage resembling Sylvia, painstakingly created through trial and error. This marks the onset of Truman’s quest for the truth – the fragments of reality are beginning to coalesce.

How easy would it have been for Truman to collapse under the weight of his disorientation and suffering? Instead, he embraces his pain and heeds its call. There’s an important lesson here. When glimmers of truth appear through cracks in the status quo – and we suffer as a result – do we validate our discontent? Or do we seek refuge in the more culturally palatable idea: that we’re deranged, deluded, broken?

Following the inner call to self-actualise might be the high road, but that doesn’t mean it looks pretty. As the saying goes, you have to break some eggs to make an omelette. Breakdowns can be a necessary stage on the path to living with purpose, authenticity and integrity.

As Alexander Lowen said, “despair is the only cure for illusion.”

Lesson 3: Embrace the unknown

When Truman is blocked from leaving Seahaven by land or air, one option remains. Despite his intense fear of water, Truman takes to the open ocean.

These final scenes always fill me with hope. In order to discover the truth, Truman musters the courage to face his greatest fear. In the same way, if we’re to thrive, each of us must face the music.

I love the scene where Cristof spots Truman’s boat. You can hear a crew member exclaim, “How can he sail? He’s in insurance!” I smile realising that Truman was likely nudged towards a career in insurance to make him risk-averse. This makes his renunciation of that manufactured identity all the more climactic.

If we’re to effectively navigate our fear, we must dance with the unknown. And in The Truman Show, the ‘unknown’ is symbolised by the ocean. Not only does the ocean represent the formless and the unfathomable, but it also stands for the endless interplay between creation and destruction. After all, the ocean is thought to be the original source of life itself. But it also has the power to silently and unforgivingly sweep life away, just as it did to Truman’s father.

This makes his voyage all the more poignant, with Truman’s rebirth forged in the crucible of oceanic chaos. He literally drowns on camera before coming back to life, at which point,we breathe a sigh of relief knowing Truman has pierced through the great unknown and triumphed over fear.

He is now free to reemerge as someone else; to recreate his life anew. When the time is right, all Truman has to do is choose.

That moment of choice rushes up to greet Truman when his boat smashes into the wall of the dome. He comes to an exit door. But just as he steps through, Cristof talks to him. He says, “Listen to me, Truman. There is no more truth out there than there is in the world I created for you. The same lies. The same deceit. But in my world, you have nothing to fear.”

We now see Cristof for who he is. Cristof has been acting out a distorted form of parental love all along. By trying to protect him from the harsh winds of reality, Cristof has stifled Truman’s growth to the extreme. Truman must now decide whether or not to disentangle from Cristof’s warped vision of truth. And that’s what he does.

Wouldn’t you be tempted to turn back? I know I would. Remember, Truman had zero knowledge of the reality beyond Seahaven. It would take serious guts to put my entire life on the line in order to be true to myself. Yet Truman embraces the unknown without hesitation. He leaves the comfortable, safe mould created for him, accepting the inevitable pain and suffering this will bring.

I always enjoy the decision to portray the exit door as a black void. Consider the difference if the writers had instead shown bright, sunny skies ahead. Blackness conveys a more realistic message: choosing freedom, authenticity and growth are daunting precisely because they ask us to embrace the unknown and the unknowable.

Here’s a question to reflect on: where in your life is there a ‘Truman door’, waiting for you to step through?

Conclusion

Truman’s existential situation isn’t different to yours or mine – in ways big and small, we all confront forks in the road.

One road is the direction of truth and understanding, while the other road perpetuates our delusion.

One road leads to enlargement of the self, while the other stifles and constricts us.

Thanks for reading. And in case I don’t see ya, good afternoon, good evening, and good night!